The Invisibility of Racial Trauma

By: Jess Ayden Li, Co-Founder & Principal Consultant

When I feel threatened, I fight. At least 75% of the time, I do. The other 25% of the time, I’m fleeing or thinking about fleeing. Rarely do I freeze or fawn. Our bodies don’t lie, and it’s often our bodies that first experience the threat — whether emotional, physical, or psychological.

A few months ago, I started attending a program that I was really excited about. The program was supposed to be inclusive and bring the liberal arts and business together. Not only was this an opportunity for me, but it would also enhance our diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging work at Healing Equity United. It was exhilarating. On the first two days of the program, I was like a sweet-toothed kid who had entered a candy store for the first time. So imagine my disappointment when white people started saying that they were surprised I spoke English “really well,” that they’ve used racist jokes to build rapport on teams at work, and called immigrants “illegals.” Comments in the following days just got worse. I reported the incidents to the program administrators about the racism I was experiencing and received little support.

On the fifth day, I was already fighting, ahem, I mean, advocating. By the eighth day, I had transitioned from fighting to wanting to flee. Ultimately, I decided not to withdraw from the program. But in doing so, I’m sacrificing my mental health.

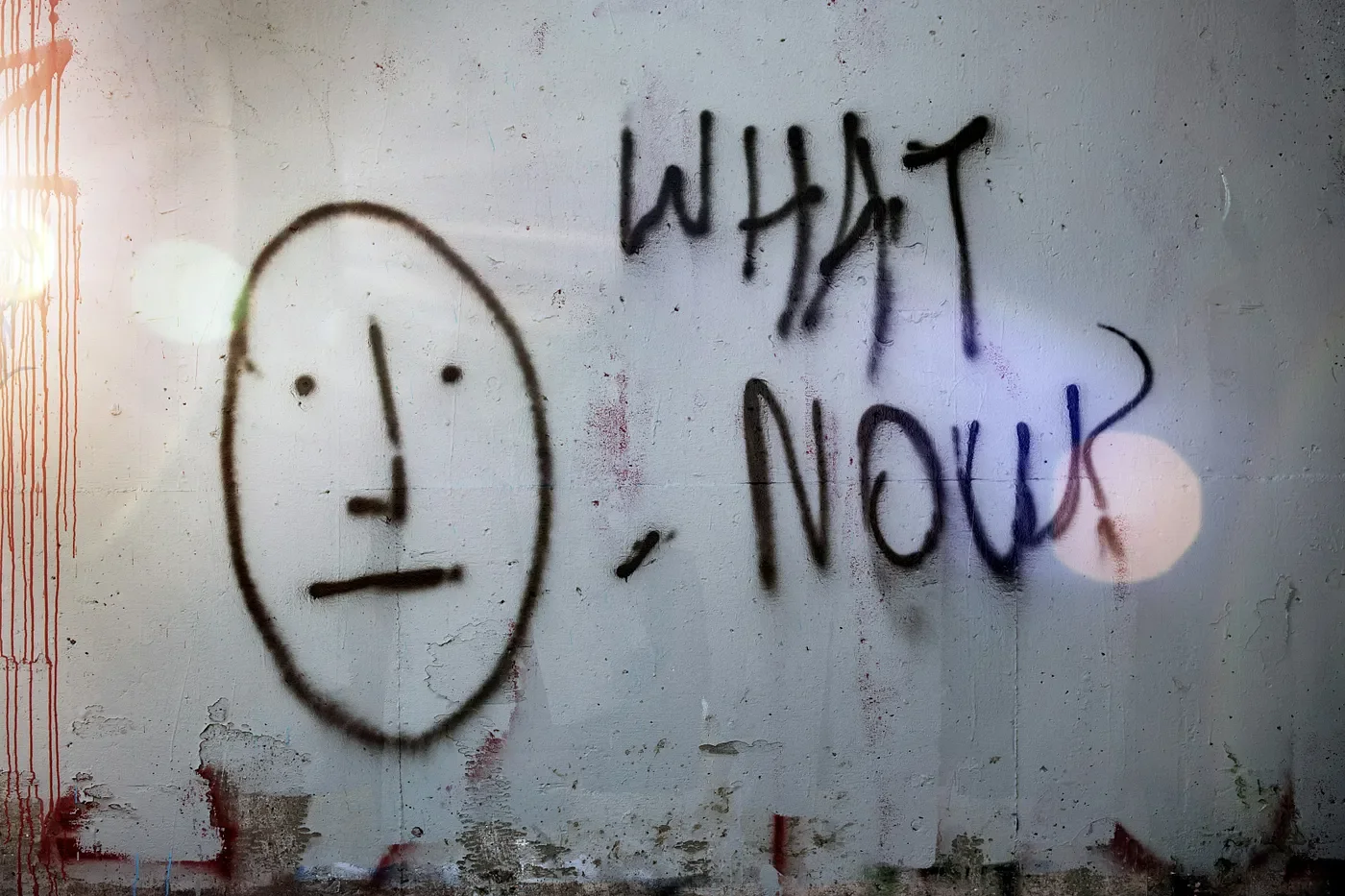

Photo by Tim Mossholder on Unsplash

Initially, I didn’t even make the direct connection between the racism I was experiencing at a micro-level with my peers and then on a macro-level with institutions. I was seen as a troublemaker. A few of the participants in the program started avoiding me. One of my team members said he didn’t want difficult people on the team. Another team member rolled her eyes whenever I spoke about anything outside our academic assignments. In one meeting, I shared that I was triggered by the Central World Kitchen aid workers being killed in Gaza. Before I could finish explaining why, that member verbally attacked me. She knew people in Gaza. She was hurt that I talked about the humanitarian aid workers as an incident that triggered me instead of the ongoing genocide against the Palestinians.

Let me be clear — I’m against the genocide and the continuing violence. And as a former humanitarian aid worker, the Central World Kitchen incident brought back images of knowing former colleagues who were killed in bomb attacks or seriously injured. But I understood where she was coming from. Hurt people hurt people. Nevertheless, I spiraled into a mental health breakdown in front of the whole team. Three days later, the team voted to have me removed. I asked why — and the response was that I just didn’t fit in.

How many of us, particularly those of us who identify as Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC)/Global Majority, have had similar experiences? How often have we been gaslit, seen as shit starters, called “the problem woman of color,” or been told that we’re difficult? How quickly do we then notice the impact of racial trauma on our mental health?

It wasn’t until the murder of George Floyd that the American Psychological Association began to address the direct correlation between racism and psychology seriously. Since then, mental health professionals have started speaking up about the effects of racism (and other forms of oppression), discussing alternative methods of healing, and working to decolonize therapy. Repeated effects of racism can have substantial impacts on our lives, and sometimes, in ways that we don’t recognize. If left unaddressed and untreated, repeated experiences of racism can cause racial trauma. Some of the signs can include:

Anxiety and hypervigilance

Difficulties with memory

Insomnia or difficulty sleeping

Distress and post-traumatic stress

Physical symptoms, i.e., migraines, stomachaches, etc.

Sad, depressed, or have suicidal thoughts

Internalized racism (believing negative messages about BIPOC/Global Majority individuals)

Decreased self-worth

Lack of energy or ability to focus, think, cope, or plan

Increased likelihood of using substances

These signs are further exacerbated for someone who already has a mental health condition. As someone living with an invisible mental health disability, I was completely unaware of how this was impacting me. I assumed that it was my disability acting up again. It wasn’t until I was talking with my mental health professionals and professional colleagues afterward that I fully understood what had happened. And when I discovered what had happened, I felt ashamed. Healing Equity United facilitates trainings on racial trauma, and yet, I hadn’t seen it. But as a mental health professional said to me recently, “It’s hard to see what’s happening when you’re in flight/fight/freeze/fawn mode because you’re just trying to survive.” One of my peers recently added, “When your disability flares up, it can be invisible even to you.”

As a community, as an organization, and as a society, we need to do better. We need to recognize and believe people when they tell us that they’re experiencing racism or other forms of oppression. We need to pause and question ourselves and our own biases when we start thinking of people as troublemakers. We need to challenge our own rules and our organizational culture if it puts up barriers. We need to lean into our fragility and discomfort. And instead of punishing those who have experienced racism, we need to hold those who are the aggressors accountable.

For those of you who are experiencing regular incidents of racism or other forms of oppression at work, at home, or in your community, I see you. I hear you. I believe you. I validate what you’re facing. It’s wrong. It’s unjust. Don’t blame yourself. Find your support system. There are others out there who understand, empathize, and will be there to advocate and hold you together.

My program ends next spring. As painful as the first few months have been, the academic experience has made me reflect and grow in ways that I didn’t expect (or at least, I would have liked to have experienced differently). On the bright side, I now have a lot of examples to use for our diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging trainings. But what I’m most appreciative of in this experience is that I’ll be leaving with a personal understanding of racial trauma in relation to ableism. And I’ll be able to breathe a huge sigh of relief and walk away knowing that at least I didn’t give up on myself in this fight.